A better way

to shift work

The most important article you can ever read about shift work

Imagine having to live opposite to the rest of the world, sleeping during the day and being awake at night. Missing family time and sports events. Being continually tired, having difficulty concentrating and unable to get enough sleep. This is shift work, and this is a way of life for many millions of people.

The circadian clock

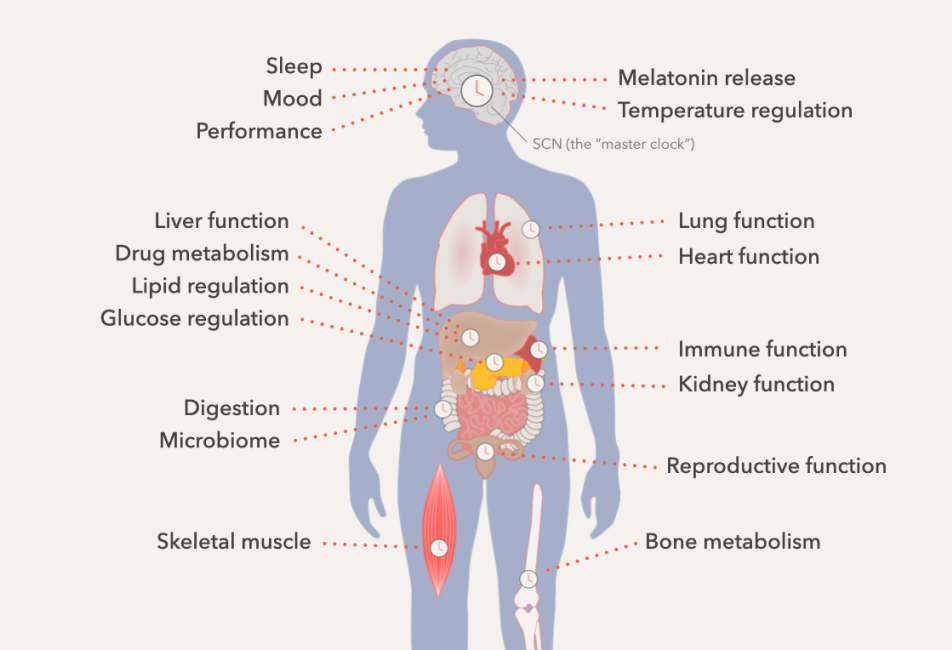

Typically, the 24-hour circadian clock in the brain keeps our daily rhythms in synch with the outside world. The clock, located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a group of around 50,000 cells in the hypothalamus, automatically generates the daily signals that control the 24-hour cycles of many systems including our sleep, alertness, metabolism, immune function and even our gene expression. Our organs – for example the heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, ovaries, and skin cells - also have circadian clocks, maintaining local function. The system can be thought of like an orchestra, with the peripheral clocks keeping time for their particular part while the SCN conducts the entire orchestra, keeping everything together.

These clocks are reset, or entrained, each and every day. The 24-hour light-dark cycle is the primary time cue that keeps the SCN clock on a 24-hour day. Meal timing also appears to help regulate some peripheral clocks, particularly those involved in digestion and metabolism. These time cues ensure that our behavior occurs at the right time of day – as diurnal animals we need to sleep at night and eat in the day to keep our circadian rhythms properly regulated.

Shift work disorder

Shift work upends this natural order. It is a relatively new phenomenon, just over a century old, and made possible by the invention of electric light. Man-made light allowed employers to override the natural rhythms of our world, extending the working ‘day’ into the night. Without this light, there is no shift work, but Edison was mistaken when he said that electric light “is in no way harmful to health, nor does it affect the soundness of sleep”. Shift work comes at a cost, primarily to shift workers’ health and wellbeing but also to safety and productivity in the workplace. Access to electricity broadens every day which, while bringing commercial and societal advances, also brings with it the concept and complications of night-work. In developing countries, the daily patterns of life that are thousands of years old are abolished literally overnight by extending the day with electric light.

Some shift work is essential. Society demands that healthcare, police, firefighters, and other emergency services be available 24 hours a day. The military is expected to be ready at a moment’s notice, night or day. Nuclear power plants cannot be shut down and restarted every day and so require continuous safety monitoring. Ships at sea need watches around the clock.

Health consequences of shift work

Shift work has consequences on health and wellbeing, however. Trying to sleep at the wrong time during the day reduce sleep duration, alters the type and quality of sleep, and affects hormone levels and metabolism. By eating at the wrong time during the night, metabolism is impaired resulting in higher levels of glucose and fats in the blood. As a result of living with such disrupted rhythms, shift workers have higher rates of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, obesity, depression, and some cancers than those who are not shift workers. Shift workers are more vulnerable to COVID-19 as the circadian control of the immune system becomes disrupted, and female shift workers have more variable menstrual cycles and impaired reproductive function, making it harder to become pregnant and maintain their pregnancy.

Other consequences of shift work

Shift workers also suffer from more mental health problems, with higher rates of alcohol, nicotine and drug use, divorce and other relationship issues. By working at night when the brain is promoting sleep, concentration and performance are worse, and accidents and injuries increase by nearly 40%. This risk does not end when you clock out – drowsy driving crashes on the drive home are an additional safety problem for shift workers due to the combination of greater sleepiness and driving close the circadian ‘dip’ in alertness in the morning hours.

Accidents related to shift work

These risks not only affect the workers themselves, however. Many high-profile industrial accidents occurred at night, including Exxon Valdez (midnight), Chernobyl (1:30am), and Three Mile Island (4am), - accidents that had potentially global consequences. As a society, we need to decide if these risks are acceptable for shift work that may not be essential; for example, are 24-hour supermarkets really necessary? Do restaurants and gyms have to be available around the clock? Do we really need live TV programming all night long? This was not the case in the past, and society managed just fine, but we now take for granted that many of these services are available 24/7 without thinking of the consequences for those asked to keep these unnatural hours. As the 24/7 society expands, the health problems associated with will continue to grow. Society should be obliged to ensure that we minimize the impact on the health and safety of those we ask to sacrifice their physical and mental wellbeing by working night and day. Yet we often don’t.

Shift work is here to stay

Shift work is not going away, however. Little is currently done to reduce the risks of shift work, and we need to find better ways to lessen its negative impact. Historically, some attempts have been made to limit the number of days at work, reducing continuous shift duration and changing the pattern of rotating shift systems. These approaches certainly have some benefits, and the implementation of a sleep- and circadian rhythm-friendly shift pattern can allow more time for sleep and make it easier for the circadian system to adapt to some extent to the shift pattern. Most workers do not have the ability to change their work patterns, however, and are stuck with shifts that are harmful to their health.

The shift work myth

The basic problem is that shift patterns, and therefore the light–dark cycle, change more rapidly than the circadian system can adapt to, resulting in wake (work), sleep and meals occurring at the wrong circadian phase. One myth that is often stated about shift work is that workers’ circadian rhythms and sleep can adapt to the nightshift schedule if they work that shift for long enough. This is not the case. It takes a day to shift the circadian SCN clock by ~1 hour and therefore there are often not enough night shifts in a row to fully reverse the circadian clock to a nocturnal schedule. For example, those working 7 nights in a row will only shift their circadian clock by 5-6 hours, less than half the 12 hours needed to fully adapt. Some specialized workers do adapt – for example when working 14 nights in a row on an oilrig or mine - but only adapt towards the end of the two-week rotation, and then have to spend the next two weeks of vacation or day shifts shifting back to normal. Living an entire life on nights, including every day off and vacation time, could theoretically allow someone to become fully nocturnal but this is not a realistic solution. Rotating shift workers have an even harder challenge with only a few days or nights working at one shift time before having to change again. In practice, no shift workers are adapted to their shift patterns, spending all or most of their time in a state of ‘circadian misalignment’ – a half-way house - where their internal circadian clocks are out of synch with sleep, work and meal timing.

It is not just ‘traditional’ nightshift workers who suffer the consequences of their work schedule. About 20% of workers have to wake up early to go to work – the ‘early risers’ – and therefore get systematically less sleep. Many people also work late and long hours, which pushes back bedtime without necessarily pushing back wake time, and then work early the next day, sometimes called ‘quick returns’, which squeeze the time available for sleep even further .

A better way to shift work

Minimizing the sleep and alertness problems and circadian disruption associated with shift work is complicated but possible. If the shift patterns can be changed, these general principles will often improve performance and safety: reducing the duration of shifts, with night shifts as short as possible; minimizing the number of consecutive night shifts (ideally to 1 but 2-3 maximum); scheduling rotating shifts in a delay direction (i.e., from morning, to evening, to night shifts); minimizing ‘quick returns’ (evening shift followed the next day by a morning shift); giving as much time off as possible after night shifts to maximize recovery sleep.

If the shift pattern cannot be changed, then there are a number of ways to help with both the cause and symptoms of shift work disorder. The Timeshifter shift work app provides this advice in a simple-to-follow plan, personalized to your individual preferences for sleep timing and duration, your chronotype, specific work schedule and whether you choose to use caffeine or melatonin.

One of the main problems for shift workers is sleeping during the day. It may be better to have the main sleep episode before work, or after work, depending on your schedule and preferences. Good sleep hygiene is a must, regardless of the sleep time, including use of an eye-mask and ear plugs, sleeping in a dark, quiet, cool, and comfortable room, turning off electronics if possible and asking people to respect your time for sleep. Melatonin can improve sleep when sleeping when ‘out of synch’ or during the day and can also help reset the circadian clock when timed correctly. Caffeine can be helpful for maintaining alertness at work, but it should be used ‘little and often’ and scheduled according to your individual plan. Bright light, particularly ‘cool’-looking blue-enriched white light, is also a stimulant and workers should expose themselves to light while at work to help maintain alertness. The light does not need to be continuous - intermittent light exposure will also help alertness and performance. Appropriately-timed light exposure and light avoidance are important to help adaptation to the shift pattern where possible, and importantly, readaptation to a day schedule at the end of the shifting sequence. The shift pattern and individual preferences will determine the exact advice each worker should follow. Napping, when timed properly, can also be an important tool to help shift workers safety and alertness. Napping before a night shift is particularly helpful in blunting the sleepiness dip many shift workers experience in the middle of the night.

It is important to avoid eating the wrong foods at the wrong time to minimize the metabolic consequences of shift work. While food is a weak time cue to entrain the SCN circadian clock, it may be important to help reset peripheral clocks and address the digestive symptoms that often come with shift work. Advice on the pattern and type of food eaten will depend on the actual shift pattern and individual preferences but in generally, eating at night when the clock is not fully adapted to the night shift (which is most people, most of the time) will cause problems, as food cannot be metabolized as efficiently at this time in the daily cycle. Studies show that in only a few days of simulated shift work in the laboratory, wrongly timed food can make a young, healthy participant have glucose levels similar to someone with diabetes, and alter the hormones that regulate appetite and food choices.

In addition to the solutions already described, new approaches are being developed to address sleepiness in the workplace. Exercise can be used as a stimulant, for example during breaks in a shift. Light, another simulant, can be used both at work and home to help maintain alertness levels. Sleep health education will facilitate better habits and better sleep hygiene, and screening work forces for occupational sleep disorders, and referring them for treatment, has been shown to improve work place safety in shift workers and will help raise the overall level of alertness and performance.

The continuum of circadian rhythm disruption

It is not just the night shift workers who suffer from circadian disruption and need help to maintain their circadian synchrony. All of us, to some extent, regularly disrupt our circadian clock even when not working nights. Staying up later on the weekend – and therefore shifting our circadian clocks later - makes it harder to get up for work on a Monday morning. Early work starts cause sleep restriction and shift our clocks to an earlier time. If school can be considered ‘work’, early school start times are even worse for teenagers whose clocks are generally set later than adults. The irregular work schedules that are common in those with multiple jobs, or part of the ‘gig economy’, also disrupt our rhythms and sleep. Some of this disruption also stems from more flexible work hours – or maybe management’s more flexible expectations – by scheduling late night or early morning meetings with people in different time zones, which in turn push the circadian clock out of synch. The greater the day-today variation in our sleep-wake (and therefore dark-light, and meal schedules), the greater the circadian disruption and the greater the risk to health and safety. Stability is the key to circadian health and getting back on track as quickly as possible after being disrupted – whether due to shift work, jet lag or any other cause - is the key goal.

New app for shift workers

Timeshifter's shift work app is an entirely new way for shift workers to optimize their sleep, alertness, and quality of life. Import your work schedule to get highly personalized advice.